The Darwin and the Art of Evolution Conference was held at the Art Gallery of NSW in September 2010. It was convened by Fay Brauer of the University of NSW and Tony Bond of AGNSW. Speakers at the two day conference covered a range of material both popular and scientific that developed around Charles Darwin’s theories in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and one session had a panel of four contemporary artists interested in Darwinian theories. I never found out why it was held in 2010 when the real Darwin action was in his bicentenary year 2009 and although I was a bit of a late entrant as a speaker I am also still puzzled about why Tony asked me if I was absolutely certain that I wanted to do it. Anyway, I was part of the contemporary artists session with Lisa Roet and her beautiful primate drawings and sculptures, Stelarc and his always astonishing technological enhancements of the human body and Brook Andrew who had been working with the 19th century aboriginal portrait photos that had featured earlier in the conference. We each gave a 20 minute talk about our own work and its Darwinian influences. What amazed me was that I was the only speaker in the entire two day conference who mentioned the word meme.

This is my paper and its accompanying slides.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

This conference is called The Art of Evolution.

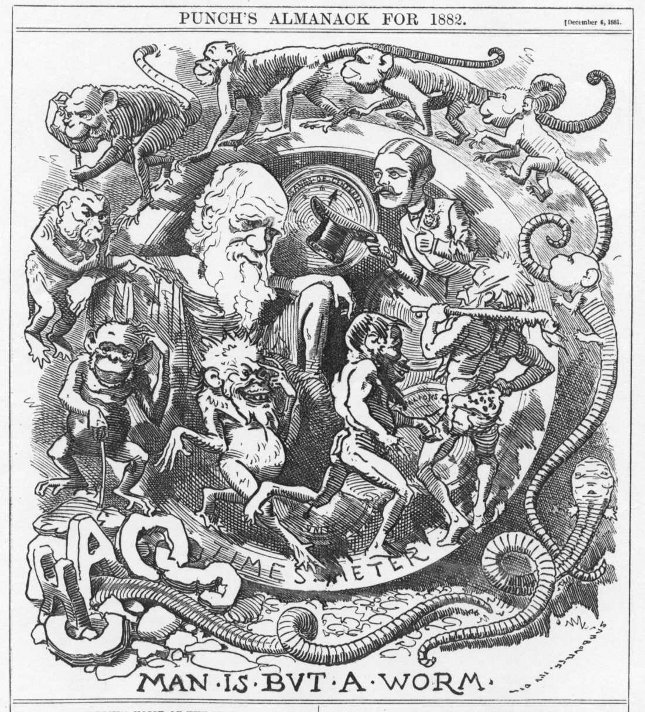

Let me start by noting that almost everything we have seen at this conference, regardless of it’s exact subject, has discussed iconography in some way.

Pretty much all of it has assumed that we are all approximately in agreement when we talk about art and artists and artworks, whatever the media and whatever their position on the high to low culture scale.

However, I’m afraid I come at this subject from an entirely different direction, seeing the range of activities that make up the art world from a view point that is known as universal Darwinism, the use of Darwinian concepts of evolution and adaptation to explain a wider range of phenomena than just organic evolution.

I think we all now exist in a culture that is awash with Darwinian concepts, most of them unacknowledged. In my early years, for instance, as a young artist I think I held a view which is pretty much the status quo in the art world to this day, a view that art was a clearly definable and distinct human activity and that within it’s boundaries it progressed, evolved into myriad styles in a way that could easily compare to a Darwin chart of the evolution of species.

This is a 1936 chart by Alfred Barr then Director of New York Museum of Modern art. Similar to an evolutionary chart for organisms but lots of cross species miscegenation you could say, and that to some extent exposes both the fallacy and the potential of that viewpoint. Indeed art styles are rather like Patricia Piccinini organisms, mixing up genes from the most unlikely forebears and producing creatures far less plausible than the platypus.

And in my early years like most young artists I combined a naively opinionated world view with an insatiable appetite for what was fashionable in art

and a belief that I could be successful by catching the wave of the latest fashionble style as it came through. Again, I think this par for the course.

There was however a bit of a reality test because I also believed that the reason styles changed was not just a question of fashion but rather that the world constantly changed and art inevitably changed to reflect that.

But let me go back slightly. I had spent most of my early childhood in a small town called Wallerawang, just below the western escarpment of the Blue Mountains between Lithgow and Bathurst. My first few years of school were there and my family had lived there for generations. It is also, I would add, on Wiradjuri land, or at least the on the border between Wiradjuri and Gundangara and Dharug country although I’m sure Brook Andrews will tell you about that.

It also happened to be the place where Charles Darwin spent more time than anywhere else in inland Australia at Wallerawang Station, the homestead of James Walker, a prominent pastoralist.

It was here that he shot (shock horror) and studied a platypus and it was here on the 19th January 1836 that he wrote in his diary about his observations of ant-lions:

…I had been lying on a sunny bank & was reflecting on the strange character of the animals of this country compared to the rest of the World. An unbeliever in everything beyond his own reason might exclaim, “Surely two distinct Creators must have been at work; their object is the same & certainly the end in each case is complete”.

This comment is probably the first indication of the line of thought that soon blossomed into the theory of evolution. What was happening here was that in the Galapagos Darwin began to realise that a single species could diverge to make use of a range of available ecological niches. In Wallerawang he began to realise that the opposite could also occur, that differing species could converge in order to exploit similar ecological niches, in other words for all its apparent eccentricity the platypus occupied a similar environmental niche as say the water vole in Britain.

I’m not entirely sure how I ever stumbled across Darwin’s connection to my hometown because it was completely unacknowledged in the area but as a result in 1969 while working at the Mitchell Library, my first job after leaving school, I found and read everything I could about Darwin’s voyage in the Beagle and the theory of evolution.

As a result of this and a range of other influences from Marshall McLuhan’s writing on media to anarchist writers like Kropotkin (Faye Brauer’s talk this morning made clear the connection between Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid and the progressive version of social darwinist thought) and the sadly under rated anarcho- syndicalist writer Rudolf Rocker I had developed a hodge podge theory of culture and cultural activism as the bedrock of human cultural evolution. In this picture art, its institutions and markets were simply a parasitic offshoot of a broader human creative impulse that itself was only part of human social ecology. I had clumsily tried to develop this viewpoint in an essay for Victorian National Gallery’s 1973 Object and Idea exhibition titled New Artist and the pursuit of a definition of what it is to be an artist has been central to my work ever since.

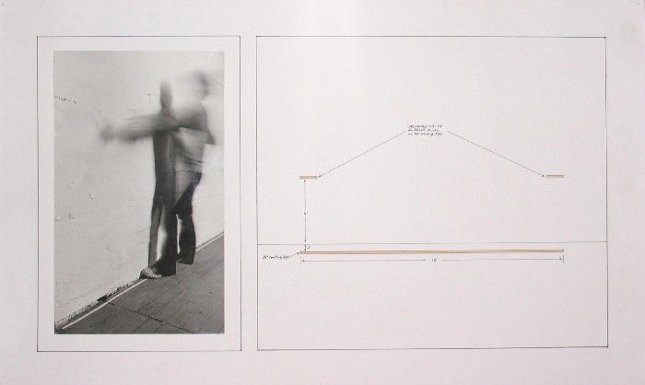

My late 60s hard edge paintings and conceptualist works had reflected this. By 1971 the work I was doing was about generating interactions between viewers in the gallery space when it occurred to me then that if my work could be considered art there were others making social and cultural interventions in the built environment on a much grander scale than I could imagine and they too should be considered as artist. I’m talking of course about the NSW Builders Labourers Federation and the Green Ban movement which was just starting to really fire up at this stage. And while the green ban movement represented an extraordinary opportunity for participatory politics involvement was, in any case, forced on me because the area where I lived on the edge of Victoria Street in Potts Point was being taken over by developers.

I became one of the founders of the Victoria Street Resident Action Group, the resident group that was subjected to the most extreme levels of violence including bashings, kidnapping and ultimately murder. But one of our actions was to set up the first urban squat since the great depression, a revival of a form of action that proliferated through inner city areas, survives to this day and has generated a number of temporary hot beds of artistic activity. The image is an article I wrote in one of our publications at the time. And I learned an important lesson. If you really are effective at threatening the status quo they will kill you. Nature is red in tooth and claw even at the level of competing ideas.

This consumed my life for around two years but after the trauma of the Victoria St experience I attempted again to develop my ideas within the art world. With the support of Daniel Thomas I began to curate an exhibition on the work of P A Yeomans, an agricultural engineer and machinery manufacturer who I described to people at the time as ‘the Australian Capability Brown” because of the way he had developed techniques for farming that worked with the natural Australian landscape rather than attempting to superimpose a european model upon it. At the time Yeomans was only known in farming circles where he was a controversial figure opposing the growing emphasis on chemical based farming but he is now seen as an almost mythical figure, the great forerunner of permaculture and industrial scale organic farming in Australia. My real point however was to make the case that cultural change, in the sense of a shift in the way we humans understand the world and act in it, is only occasionally generated in the art world yet it was the people who could produce this cultural change who should be regarded as artists. The exhibition should have been rubber stamped by the AGNSW trustees but to our shock they intervened and rejected it as “just a trade show”. As Joanna Mendehlssohn pointed out to me recently it was that same board of trustees who also rejected the donation of a Christo work because it was just a gum tree wrapped in plastic. I wondered if it ever occurred to them that their galley was full of just bits of fabric with paint on them.

From this point on I devoted my time to a range of cultural activist activities. I worked with Frank Watters on the Hunter Valley Coal project, a series of exhibitions in the Hunter valley of art and artefacts that responded to the growing threat of large scale coal mining in the valley that has now to a large extent destroyed much of the valley. I worked with Ian Burn, Terry Smith and Nigel Lendon who had just returned from New York – and a large group of others – to set up the Media Action Group producing slide shows targeted at education institutions analysing the mass media and advertising and the biased treatment of issues like uranium mining.

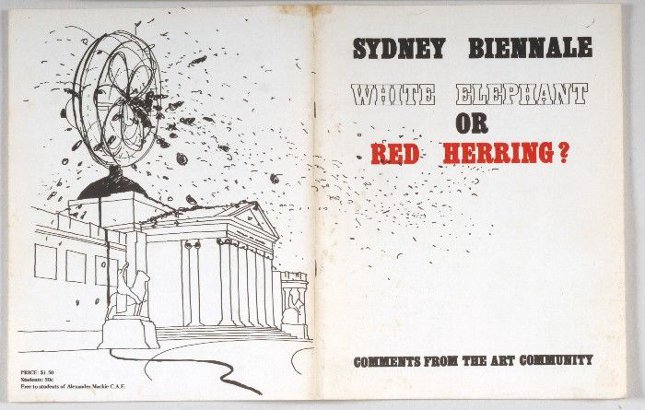

A large group of us lobbied for equal representation of both Australian and women artists in the Sydney Biennale, a movement that eventually led to us setting up the ArtWorkers Union, now amalgamated with Actors Equity and Australian Journalists Association to form the Media Alliance.

And with some Media Action Group members and a trade union journalist Dale Keeling I then set up Union Media Services where with Ian Burn and a number of other artists we developed the first Australian social marketing agency running campaigns and publications for trade unions, community groups and government departments.

One of our clients was the Australia Council who we worked closely with to develop the Art and Working Life programme supporting artists and cultural activities in the workplace and eventually one of their largest programmes.

What all these activities had in common was they involved working collaboratively in groups, they targeted areas of cultural fracture as areas of opportunity and rather than aiming to produce artworks they aimed to create ongoing social organisations and activities. In other words we were creating organisms capable of surviving and evolving in a Darwinian social ecology. I would add that we were mostly successful and many of these activities still continue in some way, have grown or else evolved into something different since we began them.

Now I’m sure many of you at this point can see where this is headed. 🙂

In 1976, a few years before this, Richard Dawkins had written The Selfish Gene where he coined the word “meme” as a concept for discussion of evolutionary principles in explaining the spread of ideas and cultural phenomena. To quote thwink.org, an online organisation devoted to analysing the processes of developing sustainability solutions

In 1976, in the final chapter of The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins dropped a bombshell. In a few quick paragraphs he sketched out what memes are, why they existed, and why they were so crucial to the study of all species whose niche dominance requires a strong culture. The potential of social engineering has not been the same since, because now we can apply all the principles of evolution to learned, memetic behavior, rather than just innate, genetically based behavior. In other words, cultural engineering is now as realistic as any other branch of engineering.

I can only agree, to me also it was a bombshell. When I finally read the book at this time in the early 80s I realised that this was what I, and the various people I had been collaborating with, had been doing, that finally there was a language to describe it. We all saw ourselves as artists but rather than creating art works like paintings or sculptures, physical objects that could be easily exhibited and traded, we had been creating new memes or reviving and adapting existing ones.

At this point I would strongly recommend the work of Susan Blackmore, her 1999 book The Meme Machine takes Dawkin’s work and explores and expands the concept of memes. To quote Wikipedia – another meme which as we know is never wrong 😉

“Blackmore’s treatment of memetics insists that memes are true evolutionary replicators, a second replicator that like genetics is subject to the Darwinian algorithm and undergoes evolutionary change.

Incidentally, I would also strongly recommend thwink.orgs paper The Memetic Evolution of Solutions to Difficult Problems.

From that we finally have the universal problem solver and proof that often the solution to a problem is often just a new problem.

I would add that my old friend Donald Brook also had a similar realisation and he has written about it extensively in recent times.

But if, as I do, you begin to define artists as cultural or memetic innovators then this also casts the art world in a rather different light as well.

For starters many people, perhaps even most, who currently define themselves as artists fall outside the category artist because they manufacture objects that conform to an existing meme. As memetic replicators rather than memetic innovators they are artisans rather than artists.

I would add diplomatically that all my other panellists here most definitely do fall into the category of memetic innovators.

On the other hand other large groups of people who would never consider themselves artists would now fall into the category of artist. PA Yeomans who I mentioned earlier is a good example.

Furthermore on that basis the institutional art world becomes barely relevant – although it is a meme in its own right it can be seen as a parasitic meme, a “selfish” meme as Dawkins would describe it, that has attached itself to the larger human impulse of cultural innovation which it then diverts and exploits to suit its own ends in much the same way that organised religion is a parasitic meme on natural human morality.

Art works also lose their position as a special category of human production, they can be seen as little more than souvenirs or relics or merchandise that are retained to remind us of the real action, the changes in cultural memes that the artist has helped bring about. In other words in this schema the relationship between the art market and real artists is pretty much the same as the relationship between the bottle collector market and beer manufacturers.

I would suggest in passing at this point that even though memetics is still a discipline in its infancy and riven with factions and complications we may well see it ultimately subsume art history and most other forms of cultural studies.

So…

if to be an artist means you must be a cultural activist of some sort, if being an artist is not defined by producing a particular sort of stuff, namely art works, that are then distributed through commercial galleries and shown in the art institutions that act as fluffers for the art market, but rather artist is a title that has to be earned through demonstrating memetic innovation, then what should an aspiring artist be doing now?

Well, as animals that are the replicators of memes we are to put it bluntly facing extinction, in fact we and our memes have brought about the likely mass extinction of much of the life on the planet.

Our ability to generate memes is the characteristic above others that has brought us to such domination of the planet, memes such as scientific method have brought us understanding, our technological memes have brought us wealth and health. But our other memes of such as consumerism, corporate personhood and extremist capitalism have brought us to the brink of complete catastrophe.

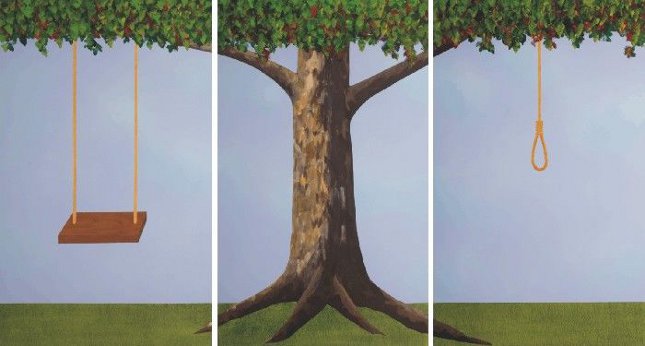

As has been discussed previously, extinction is a fundamental part of the process of evolution. On the comparatively rare occasions that I exhibit in conventional art environments, imminent death and extinction is usually my theme and has been for the last twenty years.

This is a set of large scale computer prints from 1992 called “The brief history of the human race”.

these are from the last ten years,

and this is from an exhibition this year.

But it’s not really my personal death that concerns me, it is the extinction of all that surrounds me. This fact above all is what we need to adapt to or rather what we need to adapt to avoid.

This is also from an exhibition this year.

Although extinction is as much a part of theory of evolution as successful adaptation the irony here is that we may become extinct not because of an organic failure to adapt but rather because of the inability of our memes, like extreme capitalism, to adapt.

On the other hand all memes have one delightful aspect, that they are effectively Lamarkian, they can acquire new characteristics within a generation that will then be passed on. We can all develop mutations of a meme and if we are successful in imposing them then those mutations will for a time be transmitted, at least until natural selection culls the least advantageous of them. It is within our power to change our memes and change them quite rapidly if we have the will.

With this in mind my personal choice about 8 years ago was to move back to Wallerawang,

an area that is now almost post apocalyptic, a wasteland of power stations and coal mines, a rust belt area in the bush surrounded by beautiful and spectacular mountain escarpments. And an area that is economically dependent on coal mining and coal fired power stations, an area that is in the most direct way busily constructing the end of the world as we know it. I’ve always liked to be where the action is.

My local community will directly suffer from any adoption of the only real solution to climate change, the immediate closure of the coal mining industry. If that solution is to occur, and it must occur as soon as possible, then these communities must be looked after, helped to make the transition to new economies.

My agenda has been to use my skills – artistic and political – to tackle the issues of climate change at the pointy end. I have now been appointed to the Lithgow Councils Economic Development Advisory Committee and also their Environment Advisory Committee where I am assisting in the development of new economic models for the area, models that include more renewable energy but also a role for the creative industries particularly design and content production industries, niche manufacturing and heritage tourism. And I am working with the council to develop arts projects that can carefully shift community attitudes, to help them face the inevitable.

And I’ve paid my respects to Darwin.

My wife Wendy and I set up a local branch of the National Trust which then raised money to erect a belated monument to Darwin and the unfortunate platypus whose descendants still live nearby. It’s close to the site of the homestead, now underwater beneath the ironically name Lake Wallace in a park that we have got renamed in his honour. The platypus is by a local sculptor Tim Johnman and the metalwork by another local sculptor Phil Spark.

And I also have begun exhibiting more and speaking at events like this in order to try and poke at the art world meme. Even if I believe the art system is essentially parasitic it’s single saving grace is a belief in the value of innovation, in what might be called pure cultural research even if it exists more in the PR than reality.

I would recommend a visit to the exhibition In The Balance at the MCA right now. The exhibition’s feebleness illustrates what’s wrong about art world institutions but on the other hand Lucas Ihlein’s environmental audit work, the historical campaign photography of Olegas Truchanas, the work of Catherine Rogers, Diego Bonetti and a few other works illustrate whats right, what can be done and what needs to be done.

But my personal message about the art system meme is short and one that I am sure Darwin would have agreed with if he was here.

It is simply – Adapt or die!